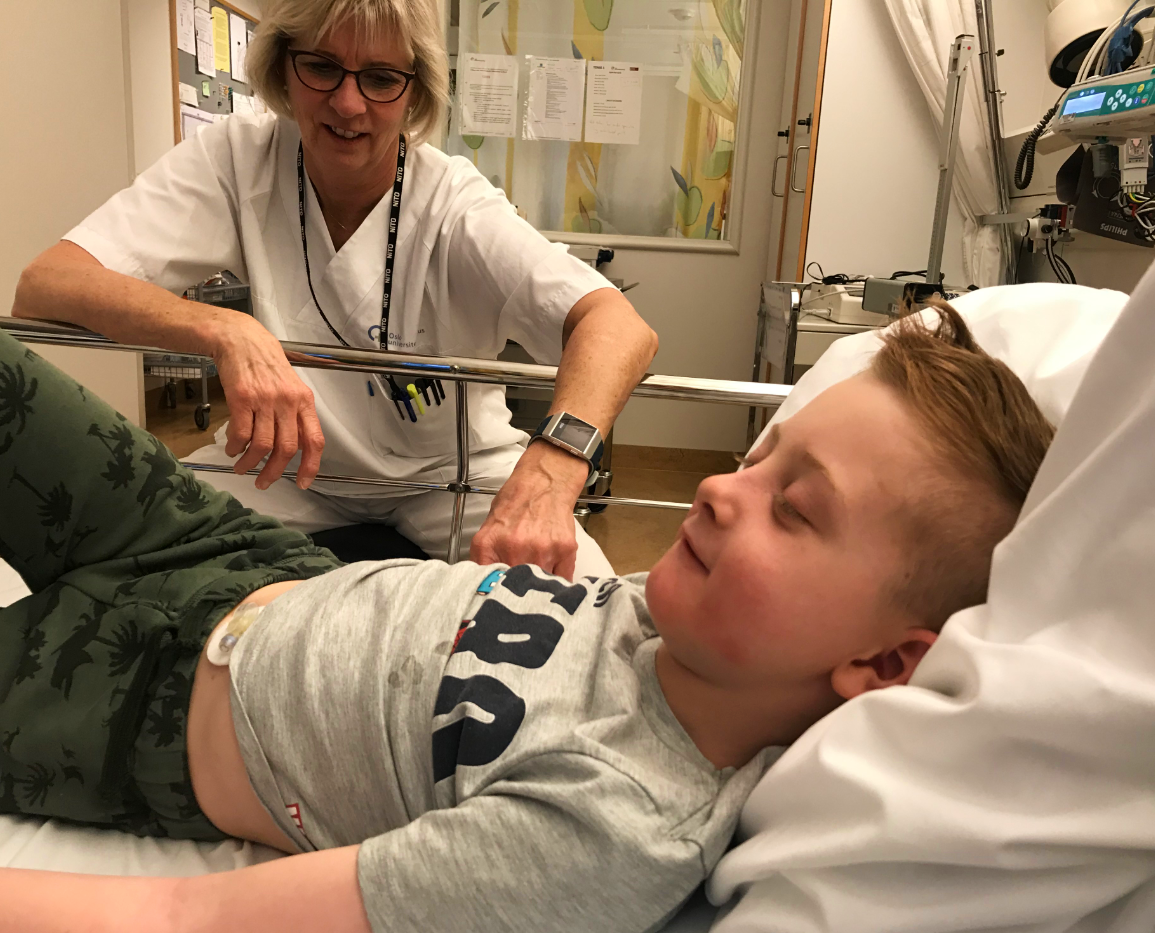

Photo: Elisabeth Kirkeng Andersen.

Five children suffering from a very rare disease are being given the opportunity to try a new drug that may help them at Rikshospitalet University Hospital. Sander, aged eight, is one of them, and he looks forward to all his visits to the hospital.

Finding the Pediatric Clinical Trial Unit at Rikshospitalet University Hospital is not easy, but after taking a lift, walking through a corridor, turning right, then left and walking down a passage, I find a nice room with even nicer people.

It is lunchtime and the whole team have set aside time to tell me more about the trial the unit, as the only one in the Nordic countries, is conducting together with a number of other countries across the world, from the USA to Australia.

‘A total of 23 children and young adults aged 3–30 years have this disease in Norway. We call it AT, an acronym for its Latin name Ataxia Telangiectasia, also known as Louis-Bar syndrome. Those affected have lowered life expectancy, and there is currently no treatment to slow the development of the disease. So it’s great that we can at least offer this trial to five children aged 6-9 years,’ says Asbjørg Stray-Pedersen. Stray-Pedersen is a senior consultant, geneticist and works in Newborn Screening at Rikshospitalet.

He is also conducting the trial on the treatment EryDex, developed by EryDel, a small Italian start-up company. The trial is randomised and double blinded, so neither she nor her colleagues know which of the children are given a placebo or the drug. Only Aase Jorun Klaveness who operates the machine that prepares the drug knows that.

The trial started in January 2019 and will run over a prolonged period. Each child receives treatment every third week at the Pediatric Clinical Trial Unit at Rikshospitalet. They spend the whole day at the hospital with their family and the staff at the unit.

Sander’s day

I return to the Pediatric Clinical Trial Unit the following week to meet one of the children, Sander, who is taking part in the trial. Sander, his mum Mariann and nine-month-old little brother Jonas and Mariann’s cousin arrive at the unit at 8.30 in the morning.

They live in Alvdal and came to Oslo a day early so they could go to the Christmas Market at Spikersuppa and for Sander to get a haircut.

‘We try to do something fun in connection with the visits to the hospital so Sander can associate them with something enjoyable,’ says his mum Mariann.

Sander was born in October 2011. His mum suspected something was wrong when he was a baby because he was so bothered by colds. The health clinic refuted this, and said he was an ordinary little boy.

It was not until 2013 that he was diagnosed with AT, and was then found to also be suffering from a type of blood cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL), a common complication of AT. The family spent a lot of time at Rikshospitalet during this period. Sander recovered from the cancer. His mum Mariann thought that his motor skills improved while he used dexamethasone in connection with his cancer treatment. Dexamethasone is one of the components of EryDex, which is being tested in the trial Sander is now taking part in.

The family had already at that point heard of the trial and that it was coming to Norway, and really hoped that Sander would be one of those selected to take part. And he was. He will spend the entire day at the hospital to be given a new dose of the drug that is being tested.

Sander is a lovely boy. Bright, trusting and cheerful. He is just six months older than my own twins. He loves dinosaurs, his favourite colour is green and he likes maths and Norwegian at school.

‘He is one of the gang at school, goes home with his pals and goes to gymnastics and used to play football,’ his mum says.

Sander is engrossed in his iPad at the hospital, but, even though I’m a stranger, he is still happy to talk to me and to the nurses who will attend to him today.

First he is weighed and then his height is measured, before he has to lie down in a hospital bed where warm bags are placed around the anterior of the elbow to make it easier to insert a venous catheter. The bags of warm water are actually hospital gloves and they can be made into fun figures if you blow them up and draw faces on them, and before long a gang of them are in the bed looking up at Sander.

His mum buys him prawns in the café which Sander eats while he looks at his iPad. He has to come here 12 times in all, at intervals of three weeks.

More common in Norway

There is a lot of AT expertise in Norway, especially at the child habilitation service at Hamar Hospital under Innlandet Hospital Trust. They follow up many of the children and use video recordings to document the development of the disease.

There are particularly many cases of AT in Hedmark County, due to a genetic variant that can be traced back to the Rendalen area. The ‘Rendal mutation’ is one of many different genetic variants in the gene that the disease is linked to.

‘This is a hereditary disease, known as autosomal recessive disorder. This means that both parents are carriers of the condition, but do not have the disease. The parents of children with AT are not usually related to each other, and do not know that they are carriers of the same disease before they have children,’ says Stray-Pedersen.

‘The disease is not immediately evident. The unsteadiness which is very characteristic of AT becomes apparent when the children are around one and a half years old. This means that many families have a second child before their first child is diagnosed. In some families, the second child is also affected,’ explains Stray-Pedersen.

However, there are indications that AT can be identified in children during ordinary newborn screening for immunodeficiency, a common complication of the disease.

‘This poses an ethical dilemma. We can diagnose the disease in babies, but there’s no treatment for it. However, it may be important for families to know about the child’s disease at an early stage. The child and family can then avoid a long investigation process, and the parents will be aware of the risk associated with any subsequent pregnancies,’ says Stray-Pedersen.

‘I dread identifying babies with AT during newborn screening as long as we have no effective treatment to offer these children, but it does provide the motivation for clinical trials. If the treatment is found to work, it will be important to start it at an early stage to slow and stop the progression of the disease,’ says Stray-Pedersen.

Two of the five participants in the trial on the new treatment are siblings. In Norway, there are five cases of siblings having the disease.

‘You must come back’

Sander and I talk about Halloween. He had a skeleton costume and I show him a picture of my children dressed up as a Zombie doctor and Hermione Granger. Then we talk about his dog, a labrador called Kitty, and I tell him about our cat Elly and that it’s her first birthday and that she’s going to have an advent calendar. Kitty is also going to have one.

Sander is still in the hospital bed. Anaesthetist Camilla comes in after a little while. She is going to insert the venous catheter in Sander, and he and his mother watch her eagerly. This can be quite a trial, because it is sometimes hard to find good veins. But Camilla succeeds at the first attempt. Sander’s mum is amazed and wants her to come back in three weeks’ time when Sander is due to be given a new round of the drug.

‘And we must give you something since you did it so well,’ says Sander.

‘It was you that did well,’ replies Merete, the clinical research nurse. Sander lay completely still and didn’t make a noise while Camilla inserted the venous catheter, and simply watched what she was doing.

Then Merete draws 50 ml of blood from Sander. The blood is going to go into a machine which may or may not mix his blood with the drug. As this is a double-blinded, randomised trial, only the person operating the machine knows which of the children will be given the drug. But Sander’s mum Mariann is convinced that Sander is one of them.

‘He has improved since we started the trial. His motor skills are better and he seems more lucid. His assistants at school say that he has more stamina and doesn’t get as tired as he used to,’ she says.

But nobody knows, apart from the woman operating the machine.

It takes around an hour and a half to mix the drug in the machine, and then the blood has to be returned to Sander’s body. In the meantime, he has to talk to a clinical research nurse who has come down from the hospital in Hamar. This is also part of the research protocol, to ensure that Sander is faring well from a mental health perspective during the trial. The rest of us leave the room while Sander talks to her.

His mum tells me that both she and her husband have relations in Rendalen. But they don’t know of anyone else in the family who suffers from the disease. Both Sander’s four-year-old little sister and Jonas are unaffected.

Hope for continued involvement

This trial is going to continue, and the Pediatric Clinical Trial Unit would be delighted to be involved.

The inclusion criteria for this phase were that the children must be aged 6–9 years, and that they had to be capable of some walking without the support of a wheelchair or someone holding their hand.

‘This age group has been selected because the children are old enough to follow instructions and for their motor skills to be tested. They also still have a lot to gain from treatment. During this age range, children with AT usually deteriorate a lot, and many of them lose the ability to walk. This also makes it challenging to measure the effect of treatment,’ says Stray-Pedersen.

Complex treatment for rare disease

‘This trial is a good example of how we in Norway can conduct complicated trials and thus help improve treatment for this patient group who are without other treatment options,’ says Siri Kolle. She is responsible for clinical trials at Inven2, and has been responsible for the research agreements for this trial.

Inven2 has drawn up the agreement for the trial with the Italian start-up EryDel on behalf of Oslo University Hospital (OUS) and Innlandet Hospital Trust.

‘What is also special about this trial is that two hospitals participate in the trial with different roles and logistics but work together as one joint research team. The Pediatric Clinical Trial Unit at Oslo University Hospital, with its expertise in conducting early-phase studies, advanced treatment methods and state-of-the-art research premises ensures that the technical implementation of the treatment is correct and in accordance with the strict guidelines for this drug,’ says Kolle, and goes on:

‘The habilitation service at Innlandet has conducted all the extensive testing of the development of the disease, which is vital to the company being able to assess whether the treatment is effective or not. This is also where the patients attend ordinary check-ups. The constant focus is on children’s experience and participation, and the quality of the data generated,’ says Kolle.

She is deeply impressed by the manner in which the trial is being conducted.

Norsk

Norsk